Google is decoupling Pixel tech from China, Plus why there's no China reset in 2026 -- China Boss News 1.16.26

Newsletter

What happened

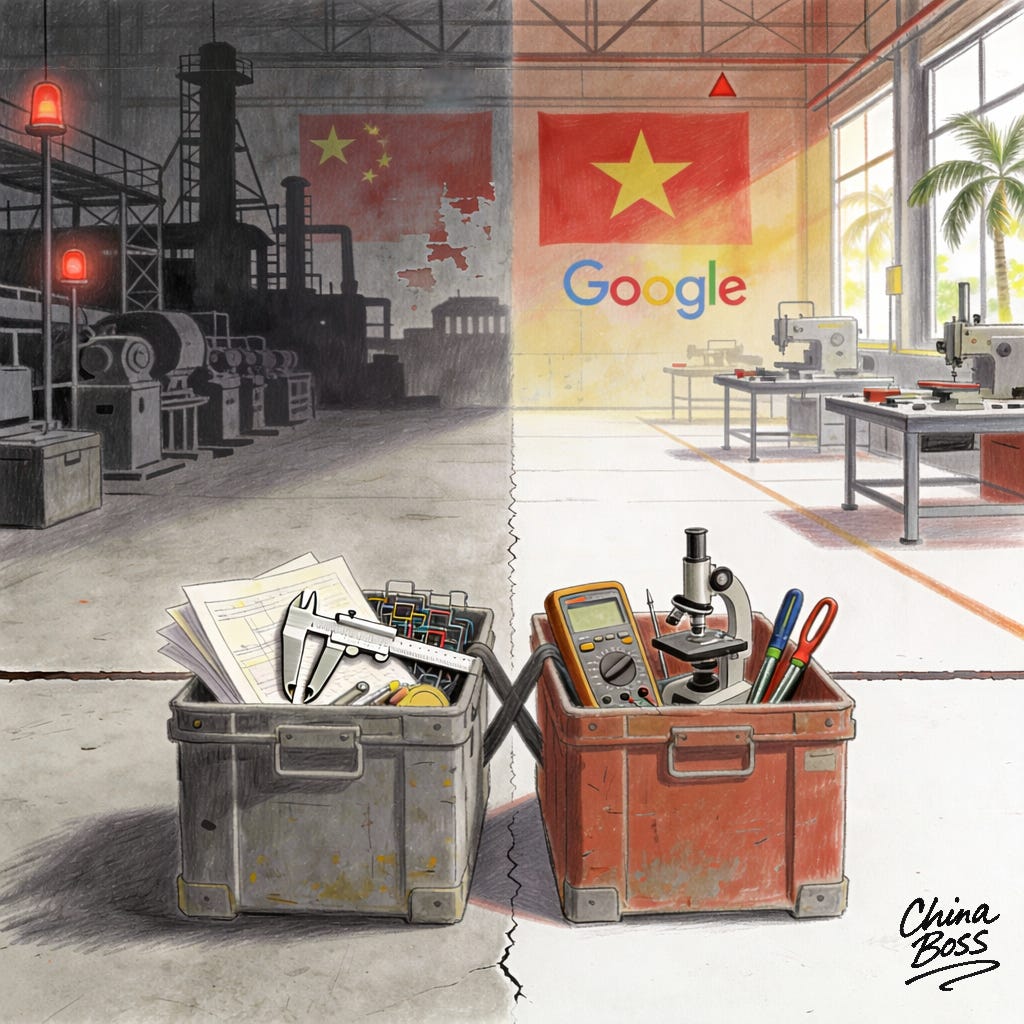

Google is taking another major step away from China.

According to Nikkei Asia, the US-based technology company—best known for its internet search engine—plans to move not only Pixel phone production but also the core development of most Pixel devices out of China and into Vietnam.

Analysts say this marks a structural shift, not a routine supply-chain adjustment.

By relocating new product introduction (NPI) to Vietnam, Google is signaling that China is no longer indispensable at the most sensitive moment of product creation—the point where design, engineering, and manufacturing lock together under pressure.

The move also exposes a widening asymmetry among US tech companies. Apple, with vastly larger volumes and deeper sunk costs, still runs parts of its NPI pipeline inside China.

Google, by contrast, operates at smaller scale and with greater flexibility.

That allows it to move faster—and to treat Pixel as a proving ground for how far de-risking can realistically go.

Why it matters

🏭➡️📐From assembly to origin

This is more consequential than a simple diversification of Google’s assembly lines.

New product introduction is the choke point of the hardware lifecycle. It’s the stage where designs stop being ideas and start becoming real products, requiring tight supplier networks, specialized equipment, and large engineering teams working under intense deadlines. If NPI fails, there is no product launch to rescue.

Google has been easing Pixel assembly away from China since 2022. Until now, however, it still relied on Chinese facilities for NPI—the phase where a phone is developed, tested, debugged, and proven ready for mass production. For every Pixel generation up through the Pixel 10, that work continued to take place in China, even when devices were built elsewhere.

That is now changing.

Going forward, Google will run NPI and end-to-end development for Pixel, Pixel Pro, and Pixel Fold models entirely in Vietnam. Only the lower-end Pixel A-series will continue to depend on China, at least for now. The shift is happening quickly, with new models expected to follow this plan from 2026 onward.

That matters because the tech industry long assumed that assembly could be moved with time and money, while early-stage development was far harder to relocate. NPI is where production limits are set, suppliers aligned, and launch timelines either hold—or fall apart.

By moving this phase, Google is signaling that China is no longer indispensable.

For Beijing, that is a strategic loss.

China’s unmatched manufacturing depth once made it the default—and often unavoidable—location for early-stage development, even for companies actively trying to reduce exposure elsewhere.

But once the learning curve migrates, reclaiming it becomes difficult—especially at a moment when regulatory discretion, data controls, and supply-chain proximity have emerged as central instruments of state influence.

🧠📉 Why China is losing the learning curve

China’s power in electronics has never rested on low wages alone. It has rested on control over commercial learning curves—the moment when engineers, suppliers, and machines learn together to turn designs into scalable products.

That knowledge is tacit and cumulative, forming where products are born, not merely where they are assembled. China has dominated this phase through dense supplier clusters that enabled rapid iteration and tooling that could be mobilized overnight.

Even as assembly shifted to Vietnam or India, the earliest and riskiest steps stayed in China because failure costs were simply too high.

But strategic rivalry has upended all of that almost overnight.

Today, the greatest threat to new product introduction is policy shock, not engineering complexity. Tariffs, export controls, data rules, and enforcement uncertainty have turned early-stage development in China into a prickly strategic vulnerability. Assembly lines can be moved with time and capital. A disrupted launch cycle cannot.

Vietnam matters because it is capable.

Google already manufactures large volumes of Pixel devices there and runs portions of the verification process locally. Contract manufacturers have expanded tooling and testing capacity, and supplier ecosystems that once looked thin are thickening. Building a phone “from scratch” outside China remains difficult—but no longer implausible.

US policy has reinforced this shift. Washington has pressed Southeast Asian manufacturing hubs to reduce reliance on Chinese inputs, increasingly linking tariff treatment and market access to how “Chinese” a product really is.

If firms can now launch complex consumer electronics outside China, the gravitational pull of China’s manufacturing clusters weakens—especially for non-Chinese brands.

This does not mean China will lose its industrial base immediately, or even quickly. But the direction of travel is changing, and with it Beijing’s leverage.

As development and launch activities move outward, supply-chain authority becomes more diffuse.

Today, de-risking and decoupling—two sides of the West’s China policy—are no longer only about where phones are assembled.

They are also about who controls the learning curve.

This Week's China News

The Big Story in China Business

WHY THERE’S NO CHINA RESET IN 2026: Three news stories last week converged on the same conclusion: the geopolitical pressures bearing down on Beijing’s economic model are not easing.