Xi Jinping's 'forever purge' has China scared stiff, Plus the 40-year ditch? China's historic investment decline to continue in 2024 -- China Boss News 1.19.24

Newsletter

What happened

“There's no end in sight” to Xi Jinping’s anti-corruption campaign that is “taking down scores of senior officials, bankers, hospital directors and even soccer administrators” in China, Wall Street Journal’s Chun Han Wong said last week.

“With echoes of Mao Zedong’s ‘continuous revolution,’ Xi has sent fear rippling through the ranks of the Communist Party for more than a decade with the largest campaign against corruption in modern Chinese history. It is now threatening to petrify the party as it tries to steer the world’s second-largest economy through its greatest period of uncertainty in a generation,” he wrote.

Last week, Fan Yifei, a former Chinese central banker was forced to admit “a ‘huge mistake,’” in a televised documentary by CCTV, China’s state broadcaster, CNN Business reported.

“The CCTV program, which aired on Tuesday as part of a wide-ranging, four-part series, detailed the extent of Fan’s alleged crimes while he was the deputy governor. It described how he had received ‘extraordinarily massive’ payments from executives of various companies in exchange for favors after taking up the PBOC’s second-highest position.”

“I wanted to possess great power, and at the same time, to be rich. I made a huge mistake,” Fan said to the camera.

Why it matters

The Great Disruptor

The impact of Xi’s attack on communist party ranks is hard to overstate. Not since Mao have China's disciplinary purges been so widespread and prolific.

Over the course of his 10-year rule, Xi has overseen a constant cleansing that has disrupted the careers and personal lives of some five million officials and business owners, according to Wong.

“In 2023 alone, the unrelenting campaign swept through the worlds of finance, food, healthcare, semiconductors and sports—taking down scores of senior officials, bankers, hospital directors and even soccer administrators. China’s foreign and defense ministers went missing in the summer before being abruptly removed from their posts, leading to suspicions that they, too, have been purged. Beijing’s recent ouster of a dozen senior military and defense-industry officials from the national legislature and a government advisory body have fueled speculation about a broader shake-up of the country’s military establishment,” he added.

But the true number of folks who find themselves upended by Xi’s “forever purge” - which experts say is more targeting of rivals than corruption - could be in the tens of millions as Xi’s gang pursue families, friends, associates, work departments, companies and municipal staff for questioning and surveillance.

In December, Politico noted that “China's security services have ramped up repression to totalitarian levels,” as their “Stalin-like purge” swept the nation.

Besides “[t]he unexplained disappearance and removal of China’s foreign and defense ministers, there have been “[o]ther high-profile victims,” like several “generals in charge of China’s nuclear weapons program and some of the most senior officials overseeing the Chinese financial sector.”

And while it has been reported that some of the aforementioned died in custody, for many Chinese - as well as foreign observers - “the untimely death of Li Keqiang, China’s recently retired prime minister — No. 2 in the Communist hierarchy — who supposedly died of a heart attack in a swimming pool in Shanghai in late October, despite enjoying some of the world’s best medical care,” was especially ominous.

Regulators and policymakers frozen

Daniel Leese, a Chinese history professor at the University of Freiburg, told WSJ that “Xi’s perpetual purges are inspired in part by Mao’s ideas on waging ‘continuous revolution,’ which were meant to avert ideological atrophy in the party and broader society.”

“But whereas Mao roused ordinary Chinese into purging class enemies and assaulting what he saw as a decaying party from the outside, Xi has shaken up the party from within, using fear to enforce virtuous behavior. Even the party’s discipline inspectors themselves have become targets, under a rectification campaign launched in February that aims to ‘turn the blade inward and cut out decaying flesh,’” he said.

But the fear is also growing out of confusion over what - if anything, under Xi Jinping - is consistently correct.

Earlier this month Beijing fired the head of the Communist Party's Publicity Department, the regulator for China's massive video games sector, after publishing rules "that sent stocks in the world's largest video games sector, including industry giant Tencent, plunging,” Reuters said.

But Xi spearheaded a campaign against the video gaming sector in 2021, which “[set] strict playtime limits for under 18s and suspend[ed] approvals of new video games for about eight months, citing gaming addiction concerns,” as part of his ongoing rectification of the tech and property sectors.

Xi raised the issue at China’s Two Sessions that year, saying “addiction to online games, along with ‘other dirty and messy things online’, could have a bad influence on Chinese juveniles because they are not psychologically mature,’” South China Morning Post said.

His “remarks were echoed by legislators” who proposed a range of measures to be implemented in the following months.

Xi’s “centralized and opaque style of governance” is having other damaging effects on China’s development.

In the recent paper, “Favor With Fear: The Distributional Effect of Political Risk on Government Procurement in China,” two Chinese researchers conclude that “insider favoritism” - officials providing favors to other officials in state-owned enterprises - rises during corruption purges, and, on a systemic level, “undermines economic efficiency and diverts resources from more dynamic private enterprises.”

But Xi’s constant attacks have also affected policymaking, as party insiders told Wong that the ‘“rule-by-fear’ approach has stifled policy debate and fueled indecision among lower-level officials.”

“Xi’s dominance ‘has made it difficult for lower officials to make decisions because they are concerned about running into trouble,’” Andrew Collier, managing director of Orient Capital Research in Hong Kong, explained.

Pile their caution onto “paying for social services, economic development, and lowering debt levels,” and it’s “an impossible balancing act,” he said.

This Week’s China News

The Big Story in China Business

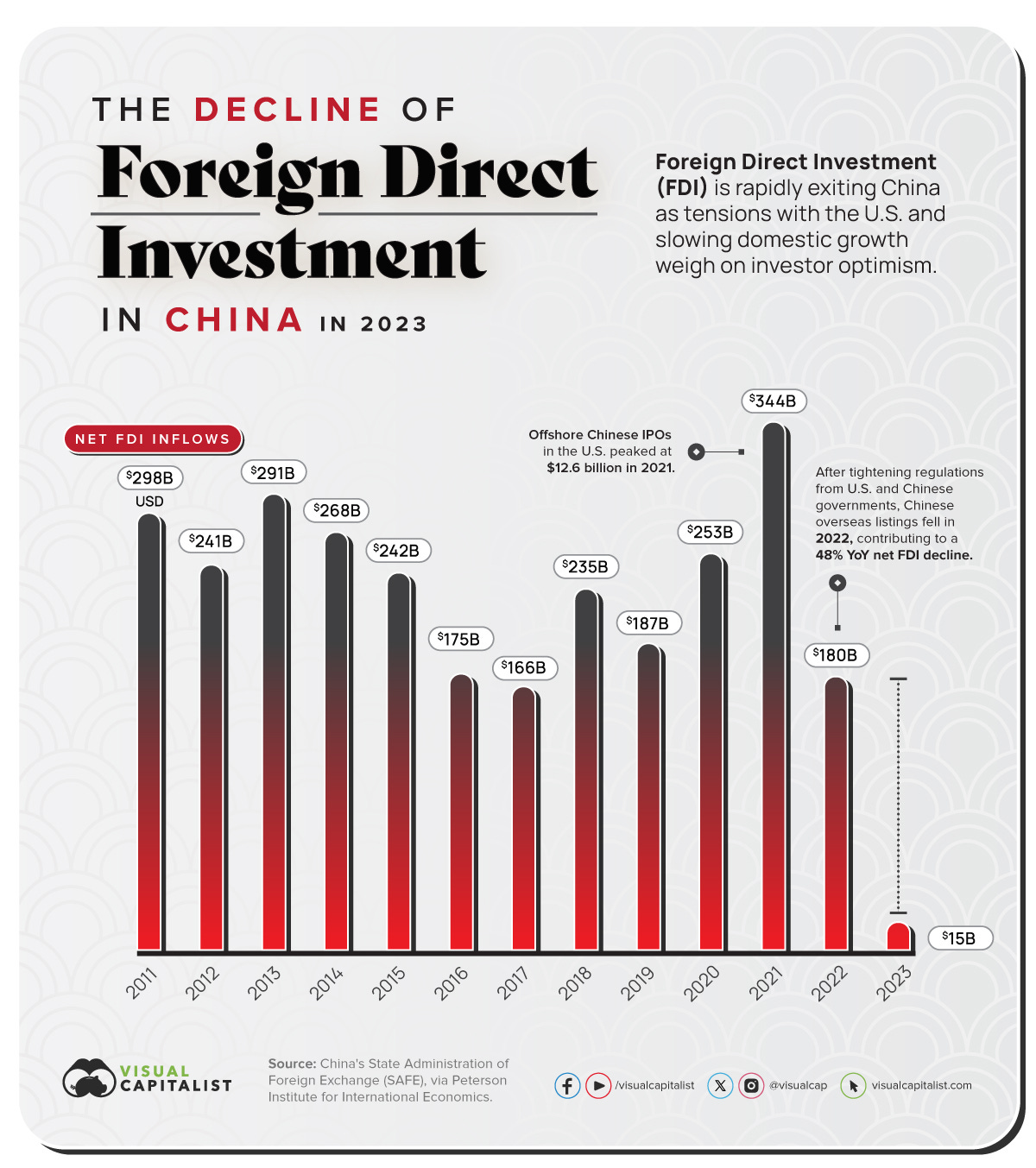

CHINA’S HISTORIC INVESTMENT DECLINE SET TO CONTINUE IN 2024: Finews Asia Editor Andrew Isbester cited data sourced from China's State Administration of Foreign Exchange (SAFE) in his dismal conclusion that “foreign investment into China practically collapsed last year.”

“In a piece by online publisher Visual Capitalist released on Thursday, the numbers tell a relatively stark, and clear, story. Since 2011, foreign direct investment inflows into the mainland hovered between $166 and $344 billion. Last year – you guessed it – they were at $15 billion,” Isbester wrote. (Emphasis added.)

From geopolitical “derisking,” a property debt crisis, and Beijing’s crackdowns on tech and foreign due diligence firms in ways that make business managers shudder, reasons for the historic drop are plenty.

And, although it may be theoretically possible to reverse - or, at least, slow the outflows - there’s little sign of improvement in the underlying factors causing them as few see a major shift in China’s tense relations with the West, improvement in its property and local government debt spirals or Beijing’s change of heart towards private industry and foreign business likely in 2024.

Historic reversal: Worse, an increasing number of analysts are wondering if China will ever get its economic mojo back.

NYT columnist Paul Krugman said yesterday that “there’s reason to believe that China is entering an era of stagnation and disappointment.”

“To outside observers, what China must do seems straightforward: end financial repression and allow more of the economy’s income to flow through to households, and strengthen the social safety net so that consumers don’t feel the need to hoard cash. And as it does this it can ramp down its unsustainable investment spending. But there are powerful players, especially state-owned enterprises, that benefit from financial repression,” he wrote.

And Ruchir Sharma, chair of Rockefeller International, in FT last November, concluded that “China's rise as an economic superpower is reversing.”

“After stagnating under Mao Zedong in the 1960s and 70s, China opened to the world in the 1980s — and took off in subsequent decades. Its share of the global economy rose nearly tenfold from below 2 per cent in 1990 to 18.4 per cent in 2021. No nation had ever risen so far, so fast. Then the reversal began. In 2022, China’s share of the world economy shrank a bit. This year it will shrink more significantly, to 17 per cent. That two-year drop of 1.4 per cent is the largest since the 1960s.”

“The biggest global story of the past half century may be over,” Sharma warned.

In other China business news

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to China Boss News to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.